Research into controlled fusion, with the aim of producing fusion power for the production of electricity, has been conducted for over 60 years. It has been accompanied by extreme scientific and technological difficulties, but has resulted in progress. At present, controlled fusion reactions have been unable to produce break-even (self-sustaining) controlled fusion reactions. Workable designs for a reactor that theoretically will deliver ten times more fusion energy than the amount needed to heat up plasma to required temperatures (see ITER) were originally scheduled to be operational in 2018, however this has been delayed and a new date has not been stated.

Research into controlled fusion, with the aim of producing fusion power for the production of electricity, has been conducted for over 60 years. It has been accompanied by extreme scientific and technological difficulties, but has resulted in progress. At present, controlled fusion reactions have been unable to produce break-even (self-sustaining) controlled fusion reactions. Workable designs for a reactor that theoretically will deliver ten times more fusion energy than the amount needed to heat up plasma to required temperatures (see ITER) were originally scheduled to be operational in 2018, however this has been delayed and a new date has not been stated.

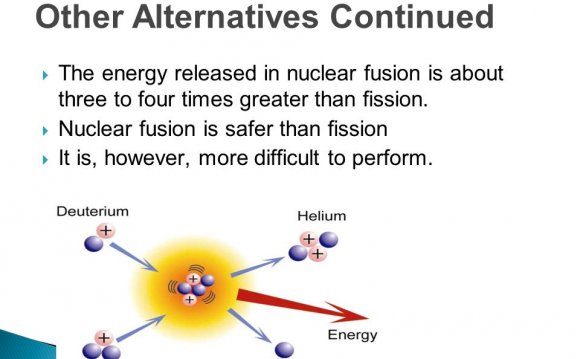

Nuclear fusion is the process by which two or more atomic nuclei join together, or "fuse", to form a single heavier nucleus. During this process, matter is not conserved because some of the mass of the fusing nuclei is converted to energy which is released. The binding energy of the resulting nucleus is greater than the binding energy of each of the nuclei that fused to produce it. Fusion is the process that powers active stars.

There are many experiments examining the possibility of fusion power for electrical generation. Nuclear fusion has great potential as a sustainable energy source. This is due to the abundance of hydrogen on the planet and the inert nature of helium (the nucleus which would result from the nuclear fusion of hydrogen atoms). Unfortunately, a controlled nuclear fusion reaction has not yet been achieved, due to the temperatures required to sustain one.

Some fusion techniques can be employed in the design of atomic weaponry and although more generally, it is fission and not fusion, that is associated with the making of the atomic bomb. It is worth noting that fusion can also have a role to play in the design of the hydrogen bomb.

The fusion of two nuclei with lower masses than iron (which, along with nickel, has the largest binding energy per nucleon) generally releases energy, while the fusion of nuclei heavier than iron absorbs energy. The opposite is true for the reverse process, nuclear fission. This means that fusion generally occurs for lighter elements only, and likewise, that fission normally occurs only for heavier elements. There are extreme astrophysical events that can lead to short periods of fusion with heavier nuclei. This is the process that gives rise to nucleosynthesis, the creation of the heavy elements during events such as supernovae.

Creating the required conditions for fusion on Earth is very difficult, to the point that it has not been accomplished at any scale for protium, the common light isotope of hydrogen that undergoes natural fusion in stars. In nuclear weapons, some of the energy released by an atomic bomb (fission bomb) is used for compressing and heating a fusion fuel containing heavier isotopes of hydrogen, and also sometimes lithium, to the point of "ignition". At this point, the energy released in the fusion reactions is enough to briefly maintain the reaction. Fusion-based nuclear power experiments attempt to create similar conditions using far lesser means, although to date these experiments have failed to maintain conditions needed for ignition long enough for fusion to be a viable commercial power source.

Creating the required conditions for fusion on Earth is very difficult, to the point that it has not been accomplished at any scale for protium, the common light isotope of hydrogen that undergoes natural fusion in stars. In nuclear weapons, some of the energy released by an atomic bomb (fission bomb) is used for compressing and heating a fusion fuel containing heavier isotopes of hydrogen, and also sometimes lithium, to the point of "ignition". At this point, the energy released in the fusion reactions is enough to briefly maintain the reaction. Fusion-based nuclear power experiments attempt to create similar conditions using far lesser means, although to date these experiments have failed to maintain conditions needed for ignition long enough for fusion to be a viable commercial power source.

Building upon the nuclear transmutation experiments by Ernest Rutherford, carried out several years earlier, the laboratory fusion of heavy hydrogen isotopes was first accomplished by Mark Oliphant in 1932. During the remainder of that decade the steps of the main cycle of nuclear fusion in stars were worked out by Hans Bethe. Research into fusion for military purposes began in the early 1940s as part of the Manhattan Project, but this was not accomplished until 1951 (see the Greenhouse Item nuclear test), and nuclear fusion on a large scale in an explosion was first carried out on November 1, 1952, in the Ivy Mike hydrogen bomb test.

Research into developing controlled thermonuclear fusion for civil purposes also began in earnest in the 1950s, and it continues to this day. Two projects, the National Ignition Facility and ITER are in the process of reaching breakeven after 60 years of design improvements developed from previous experiments.

Research into developing controlled thermonuclear fusion for civil purposes also began in earnest in the 1950s, and it continues to this day. Two projects, the National Ignition Facility and ITER are in the process of reaching breakeven after 60 years of design improvements developed from previous experiments.

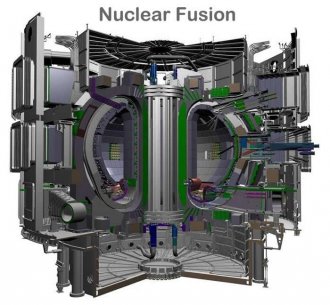

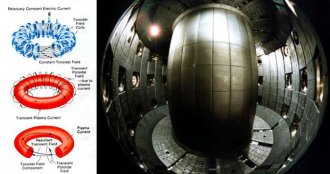

The best results were obtained with the Tokamak-type installations (see the Figure below).

ITER: the world's largest Tokamak

ITER is based on the 'tokamak' concept of magnetic confinement, in which the plasma is contained in a doughnut-shaped vacuum vessel. The fuel—a mixture of deuterium and tritium, two isotopes of hydrogen—is heated to temperatures in excess of 150 million°C, forming a hot plasma. Strong magnetic fields are used to keep the plasma away from the walls; these are produced by superconducting coils surrounding the vessel, and by an electrical current driven through the plasma.

The origin of the energy released in fusion of light elements is due to an interplay of two opposing forces, the nuclear force which draws together protons and neutrons, and the Coulomb force which causes protons to repel each other. The protons are positively charged and repel each other but they nonetheless stick together, portraying the existence of another force referred to as a nuclear attraction. The strong nuclear force, that overcomes electric repulsion in a very close range. The effect of this force is not observed outside the nucleus. Hence the force has a strong dependence on distance making it a short range force. The same force also pulls the neutrons together, or neutrons and protons together. Because the nuclear force is stronger than the Coulomb force for atomic nuclei smaller than iron and nickel, building up these nuclei from lighter nuclei by fusion releases the extra energy from the net attraction of these particles. For larger nuclei, however, no energy is released, since the nuclear force is short-range and cannot continue to act across still larger atomic nuclei. Thus, energy is no longer released when such nuclei are made by fusion (instead, energy is absorbed in such processes).

Fusion reactions of light elements power the stars and produce virtually all elements in a process called nucleosynthesis. The fusion of lighter elements in stars releases energy (and the mass that always accompanies it). For example, in the fusion of two hydrogen nuclei to form helium, seven-tenths of 1 percent of the mass is carried away from the system in the form of kinetic energy or other forms of energy (such as electromagnetic radiation). However, the production of elements heavier than iron absorbs energy.

Research into controlled fusion, with the aim of producing fusion power for the production of electricity, has been conducted for over 60 years. It has been accompanied by extreme scientific and technological difficulties, but has resulted in progress. At present, controlled fusion reactions have been unable to produce break-even (self-sustaining) controlled fusion reactions. Workable designs for a reactor that theoretically will deliver ten times more fusion energy than the amount needed to heat up plasma to required temperatures (see ITER) were originally scheduled to be operational in 2018, however this has been delayed and a new date has not been stated.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE