Representatives from the seven regions that are backing ITER – the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor – met for only the second time at the site of the planned reactor in southern France in September to underline the importance of the project.

Representatives from the seven regions that are backing ITER – the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor – met for only the second time at the site of the planned reactor in southern France in September to underline the importance of the project.

‘Not to invest in fusion would be a big mistake, ’ said Günther Oettinger, the European Commissioner for Energy. ‘We have oil for the next 20, 30, or maybe 40 years; but nobody knows what will happen at the end of the century. We have to switch and we need to invest in new, innovative energy generating technology for our children.’

ITER aims to produce energy through the same nuclear reaction that powers the sun. But, while the centre of the sun burns at 15 million degrees Celsius, the hydrogen inside the ITER reactor will be heated to some 150 million degrees Celsius.

At that temperature, electrons are ripped off individual atoms to form plasma, where nuclei float in a sea of electrons.

The high temperature means the plasma cannot be allowed to touch the sides of the reactor. So it will be suspended amid a vacuum in a toroid – a doughnut shape – using some of the world’s most powerful magnets.

‘The magnetic field will put very high mechanical stress on the supporting structure, ’ said fusion physicist Dr Osama Motojima, ITER's Director-General. ‘So we developed an engineering design almost close to the limit of the material.’

Vast rewards

The potential rewards of the project are vast: fusion-based power would solve much of the world's energy needs without the dangers of traditional nuclear reactors.

But the difficulty of the technology means it will take time. ITER is aiming to start the most important test reactions in 2027. Success then will mean simply that the principle has worked so that plans can begin to construct commercial reactors to supply electricity grids. These might not come on line till 2040 or later.

‘We have oil for the next 20, 30, or maybe 40 years; but nobody knows what will happen at the end of the century. We have to switch and we need to invest in new, innovative energy generating technology for our children.’

Günther H. Oettinger, European Commissioner for Energy

Work began in 2010 on the 42-hectare site in Saint Paul-lez-Durance, in the hills of Provence, France, where China, the EU, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States are collaborating on ITER.

So far, a five-storey headquarters building and an assembly building have been built, and the foundations have been prepared for the main reactor.

Less hazardous

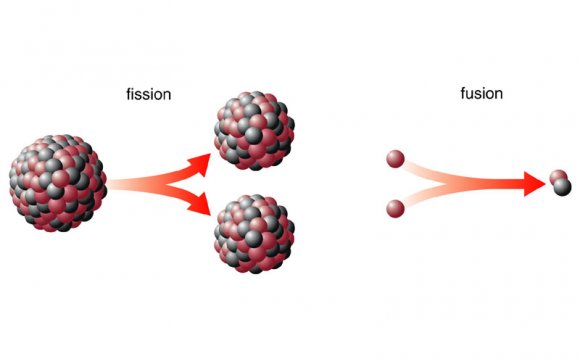

The reactive materials used in fusion are less hazardous than those for traditional fission reactors. Fission occurs when a large nucleus splits, giving off energy, and it normally uses radioactive forms of uranium, which pose a threat if the reaction leaks.

The fusion reactions being worked on consist of two small nuclei – of hydrogen – which collide to form helium, giving off energy in the process. Though some of the hydrogen used will be radioactive – the reaction needs heavier isotopes than the most common form of hydrogen – it will be easier to store and manage than uranium. Moreover, only tiny amounts will be needed because of the huge amounts of energy given off in the reactions.

However, mastery of nuclear fusion has proved elusive for half a century. Fusion reactions have been achieved in other test facilities, such as JET, the Joint European Torus, in the United Kingdom. But these runs have lasted just a few seconds.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

![Golden Sun (Blind) *w/ Serahbear*: [74] Fission Finish](/img/video/golden_sun_blind_w_serahbear_74.jpg)