Construction has been cleared by DOE officials to start immediately, six months ahead of schedule. Plans originally had called for the work to begin after the conclusion of a series of experiments on the NSTX tokamak. But when technical difficulties delayed the start of the experiments, PPPL managers decided to move directly to the upgrade rather than spend an undetermined amount of time addressing the technical issue. Specifically, a short that damaged a key piece of magnetic equipment would have been expensive and time-consuming to replace.

Construction has been cleared by DOE officials to start immediately, six months ahead of schedule. Plans originally had called for the work to begin after the conclusion of a series of experiments on the NSTX tokamak. But when technical difficulties delayed the start of the experiments, PPPL managers decided to move directly to the upgrade rather than spend an undetermined amount of time addressing the technical issue. Specifically, a short that damaged a key piece of magnetic equipment would have been expensive and time-consuming to replace.

Work on the upgrade has brought excitement to the technicians and engineers at the laboratory. "We're building something that's one of a kind, that hasn't been built before, " said Michael Williams, associate director for engineering and infrastructure at PPPL.

Fusion takes place when the atomic nuclei in plasmas combine at extremely high temperatures and release a burst of energy. Such reactions drive the sun and the stars. But sustaining fusion in the laboratory has proven quite difficult because plasmas that leak from the confinement can halt the reaction. Controlling the plasma is thus a basic goal of fusion research.

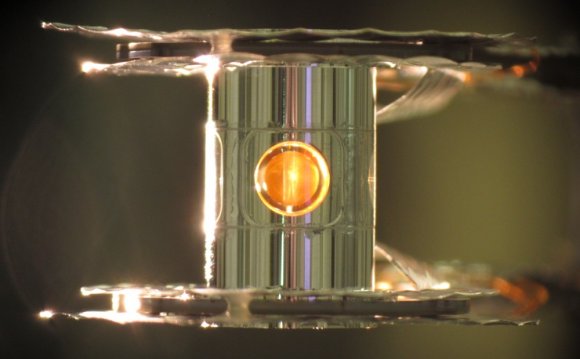

PPPL physicists will use the NSTX upgrade to assess the role of the compact reactor for the future development of fusion power. The spherical NSTX torus confines its plasma in the shape of a cored apple, unlike bulkier conventional tokamaks that produce doughnut-shaped plasmas and can be more costly to construct.

PPPL scientists are eager to explore mysteries that have puzzled them for years. A key issue is whether the NSTX reactor can maintain its record-high level of a measure called "beta" — the ratio of the pressure of a plasma to the strength of the magnetic field that confines it — as the plasma grows hotter. The higher the beta, the more cost-effective the confinement.

The NSTX upgrade will furnish new tools for probing such issues. The overhaul "will provide ample research opportunities for five to 10 years' worth of work at least, " said Michael Zarnstorff, deputy PPPL director for research. "The whole NSTX group is quite excited by the opportunities and the leadership position that it will be in."

The makeover will boost the principal capabilities of the NSTX reactor, which began operating in 1999. The device puts high-voltage current into an isotope — or form — of hydrogen gas to make the intensely hot plasma that is confined inside the reactor's magnetic field. The upgrade will double the field strength to one tesla — or 20, 000 times the strength of the Earth's magnetic field. The electric current flowing in the plasma will also double and reach 2 million amperes. By contrast, a 100-watt light bulb draws one ampere of current.

Achieving these increases calls for widening a stack at the center of the reactor that puts current in the plasma and helps to complete the magnetic field. Widening the center stack also will increase the electric pulse that drives the plasma current from one second to five seconds, giving researchers more time to study the plasma.

The enhancements will help double the temperature at the core of the plasma to at least 20 million degrees Celsius, or twice the approximately 10-million-degree Celsius core of the sun. New heating also will come from installation of a second device called a "neutral beam injector" to go with the one currently on the machine.

The increased power will enable PPPL scientists to tackle these major questions:

- Can the compact device continue to effectively contain plasma when the temperature rises, which could make the confinement more difficult? Greater heat will reduce the rate at which plasma particles collide with one another — a phenomenon called "collisionality" that could further hinder the confinement. If the upgrade can effectively control the hotter plasma, "that means we could achieve high fusion power in a pretty compact machine, and that could make machines cheaper in the future, " said Jonathan Menard, a principal research physicist and program director for the NSTX.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE